A History of Hunger

Hunger and malnutrition has haunted humanity for as long as we can remember. It was once an extremely common problem, striking every inhabited continent in the world.

Famines, the direst of hungers, became more common after societies adopted the risky business of agriculture. The success of farmers changed with the weather, literally, and not feeling full at the end of the day was so common that it was considered part of the human condition. What you cannot change is something that you may as well accept.

Though famines and hungers typically began witht the onslaught of natural disaster, such as drought, floods, and disease outbreaks, or the human business of war and politics - though the lines have become more blurred the more of an impact humanity has had on nature - they often seem to have been made worse by the poor social attitudes of more fortunate onlookers.

History shows us that neighbours and authorities often callously turned the other cheek once disaster had struck, for no other reason than the shame and humiliation thrust upon the starving. The catastrophic Finnish and Swedish famines of the 1800s, for example, could perhaps be considered social tragedies, too. They were the last natural famines to occur in Europe and were instigated by strangely cold weather and drought. By Midsummer, there was still snow lying on the ground in northern parts of the country. The disruption to agricultural process was enormous, leaving thousands of empty bowls across the two countries, causing many to die prematurely.

The farmers afflicted went without sympathy and compassion. In Sweden, only people who were judged to be able to work for, or else later repay the aid available, were considered eligible to receive it, and across the Baltic Sea, the suffering of the Finnish victims was explained as divine punishment for the sins that they had evidently committed. These widespread hungers were not treated like the problem of larger society but something that fell in the lap of the individual person, family, or community afflicated. The hungry were entirely isolated.

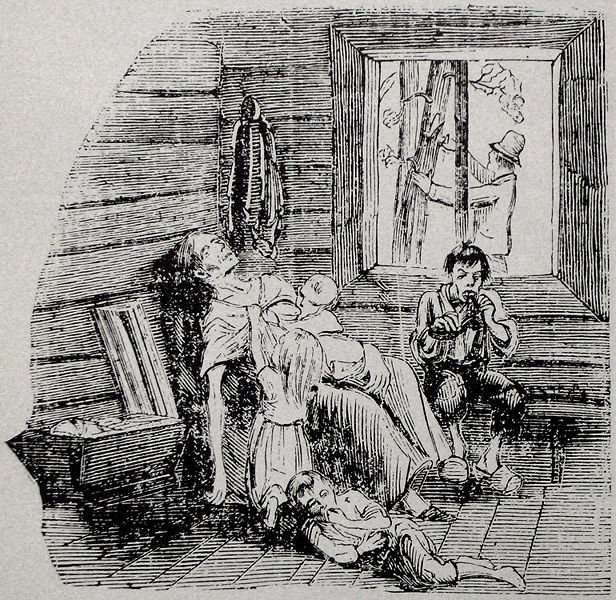

An 1867 engraving depicting the Swedish famine of 1867-1869. Starvation and widespread poverty contributed to the emigration of more than one million Swedes to the United States. The man outside the window is presumably removing bark from the trees to eat, for lack of anything else.

Image: Wikimedia Commons

One of the most interesting parts about studying the past, from my perspective, has not always been discovering how different lives have been and how much our societies have developed. It can be just as interesting to see how similar things have remained throughout thousands of years. Poor attitudes towards hungry fellow members of society is an old human behaviour that we can trace back to 4,000 years ago and the earliest agricultural society known to us, located in the region we today call Iraq.

Ancient Mesopotamia was, despite its reputation as an efficient state system running on grain, affected by an alarming amount of food insecurity. Seth Richardson, historian of ancient Mesopotamia at the University of Chicago, has found the presence of hunger in cities across the region, revealing that it was, even then, an issue that society was perpetuating onto the poor. Like in Finland and Sweden thousands of years later, hunger was treated by onlookers as the problem - even the fault - of those on the margins of society. Though gods, kings, and grand institutions were celebrated as caretakers of their citizens when harvests happened to be good, they were not necessarily seen as responsible for the food insecurity that plagued the less fortunate.

As rulers seem to not have bothered very much with this societal ill, marginalised hunger shows up very little in official records. In order to find the hungry we instead have to look at private letters sent by ordinary citizens. I found these letters intriguing to read. Most of us probably associate trolling with social media and online culture, but these letters show an excellent amount of ancient rudeness. There was plenty of sneering and contempt for the hungry who wrote to ask for help. One man is berated for being late with planting his field and another is mocked for being needy and lazy. Although men evidently found themselves in economic trouble most letters were actually written by women - a more vulnerable group in society, then as now - and often about their children. Richardson means that they never asked for more than what they were due and only that the state met its own promise to provide enough protection for its citizens. The responses they got were chilly.

Hunger has physical symptoms that debilitate our ability to function, but it was not seen as an illness by the authorities. Its victims were seen as morally faulty. Coming back to drawing parallels between ancient societies and the ones we live in today, it becomes fairly easy to notice a few between the plight of hungry ancient Mesopotamians and our own global, as well as local, food situation in the 21st century. Though thousands of years have passed between ourselves and those early states of ancient Mesopotamia, we have not necessarily gotten better at equitable food distribution. Our global food production is enough to feed the entire human population of nearly 8 billion people, but hunger remains an isolated issue, confined to certain countries and communities across the planet.

According to the Global Hunger Index, 11 countries in the world today are currently facing alarming levels of hunger. An estimated 690 million people across the globe suffer from malnutrition. Covid-19 has certainly not made things better. Starvation, though increasingly rare, may become reality for thousands as fragile governments in Syria, Yemen, Somalia, South Sudan and others struggle to curb the effects of the virus. The problem is both global and local. Whilst famines no longer occur in richer parts of the world, food insecurity stalks corners of major Western countries, too. It took a famous footballer to convince the British government to continue providing children with free school meals to fight hunger during lockdown. In France, ca. 10% of the population are believed to experience food insecurity on a weekly basis under normal circumstances. At the same time, we throw away more than 900 million tonnes of food each year.

Our global hunger problem is clearly no longer an unfortunate effect of bad weather. Even where famines strike because of drought can we share resources and prevent hunger. We live in a world that produces more food and is more developed and connected than ever before - by airplanes, ships, cars, and digital technology - but we have the same tendency to isolate and deflect our shared hunger problem as we did thousands of years ago. In some ways we are much the same.

We should not the dismiss the progress we have made. Hunger is on the decline. But where it still exists we can see the same ancient tendency to look the other way.